|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Contents of this Chapter: | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 'And There's More Where That Came From!

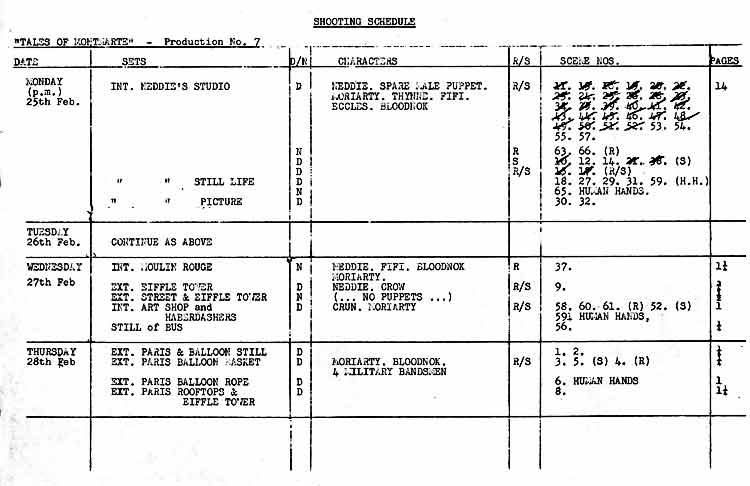

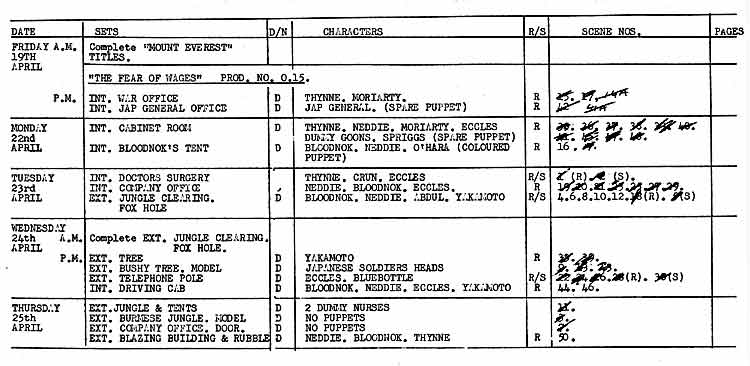

'After Blue Streak We Give You Brown Stain...' Puppet Lip-Synch Story... The Tale of the Revised Pilot Film... A Family Affair... General Production Stills... Production Stills From The Ascent of Mount Everest (s01e01)... Production Stills From The Fear of Wages (s01e03)... Production Stills From The Hastings Flyer (s01e09)... Shooting Schedules... |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

'And There's More Where That Came From!' |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| During the second half of the 1950s,

the number of television receivers in the UK rapidly increased, with a

corresponding decrease in the size of the radio

audience. As a result, the radio scene was rapidly changing, putting increasing pressure

on artists to reinvent themselves in the new medium, or fade into entertainment obscurity.

Unfortunately, but perhaps not totally unexpectedly, attempts at bringing Goon-type

humour to the television screen were only moderately-successful. The first of these were

three short series directed by Dick Lester (The idiot weekly price 2d., A

show called Fred, and Son of Fred, all 1956). They included only Peter Sellers

and Spike Milligan, because Harry Secombe was unavailable. Although these shows had some

amusing moments, they were not able to come close to accommodating Milligan's

imagination. A major factor was that television at that time was still largely a 'live'

medium. Other attempts were Kenneth Carter's short series, Yes, it's the cathode ray

tube show (1957), and Brian Tessler's single program, Secombe and friends

(1959). Again, they included only part of the Goon team. Interestingly, all of

the shows mentioned were produced by Associated- Rediffusion Television (ITV), rather than

the BBC, so were not allowed to use a certain G-word ("Goon"

is a BBC copyright). Not surprisingly, therefore, the Goons had been thinking in the direction of some sort of animation to provide them with a television vehicle. So when Tony Young of Grosvenor Films suggested using rod puppets and string puppets, together with stock film and animation, the idea found favour with Spike Milligan, in particular. But the idea may have seemed too radical for the BBC, for on the proposal?s first go round in late 1959, they had turned it down flat. The proposal was then put in front of ITV?s Associated-Rediffusion Television but they got a case of cold feet (a disease thought to be caused by the low ratings obtained by the Fred shows). Then the BBC was asked again, and this time they were found to be interested after all. It is quite possible that what changed minds at the BBC was the pilot film, made with private money in February 1960 (see sidebar). In any case, an agreement to proceed with the Grosvenor Films proposal was reached, and the series was finally given the green light in November 1961. The deal was sealed with an advance of enough funds for the first 13 of the 26 episodes, with financing for the second 13 to follow. The agreement even contained an option (never taken up) of a further 26 episodes. We can only guess at which Goon Shows would have been chosen for another 26 episodes! At 33 minutes long, the pilot film, The Lost Colony, was more than twice as long as the series episodes that would follow (and was itself later cut down to the standard length). This was due not only to the pilot's use of the radio Goon Show recording, The Sale of Manhattan, for the soundtrack (approximately 27 minutes without the musical interludes), but also the relative slowness of the puppets. This latter problem, for which there was no practical solution, basically killed Tony Young's original proposal to reuse the BBC's Goon Show recordings for the series. As it happened, the BBC would not release any Goon Show recordings for this purpose, so the only alternative was to record new ones. However, in order to meet the 15 minute run-time requirement and the special needs of the puppets, not forgetting the need to take advantage of the visual medium of television, it was obvious that new scripts were going to be needed as well. Therefore, in a task that probably took up most of 1962, twenty-six Goon Show scripts were selected, and under the editorial hand of Maurice Wiltshire, these were re-worked and cut-down to the required 15-minute puppet format. Befitting of television comedy, a lot of visual humour did find its way into the new scripts. With a project this large, Grosvenor Films needed to rent suitable studio space. This was found at 208 Kensal Road, Westbourne Park, London (map), upstairs in the On-The-Spot Lighting Equipment building. Considering that just outside the side door was the Grand Union Canal, it is not surprising that one of the Goon Shows chosen for The Telegoons was The Canal. Of course, in those days the canal was nothing like the picture postcard it is today, considering that London's canals had fallen into a serious state of decay by the late 1950s or early 1960s. Nevertheless, this was an ideal spot for the making of The Telegoons films--a good choice of lights were available downstairs (On-the-Spot's main business was renting lighting equipment to the film and television industry), and just around the corner were (and still are) the junk shops of Golborne Road, where some of the on-going search for small "puppet-scale" property items probably took place. But the sad news, folks, is that the On-the-Spot building was demolished about 1990, and the site has been standing vacant since then. Current plans for the site include a canalside shop/gallery complex with 100 studio work spaces (see side bar). It is not to hard to imagine, therefore, that one day visitors to this future facility may see a commemorative wall plaque which will read, "The Telegoons, produced by Tony Young, Grosvenor Films Ltd., in association with BBC-tv, filmed on this spot, 1963". Starting in January 1963, film production continued through July. Six months of actual filming produced, on average, one 15-minute episode per week. Twenty-six episodes were filmed, and the show premiered on BBCtv, on Saturday October 5, 1963, at 5:40 p.m. Despite some criticisms, the series was very popular with the 9- to 17-year olds, and still remains the most successful attempt at bringing the Goon Show characters to television. Apart from the contribution of their voice talent, the Goons (Spike Milligan, Harry Secombe and Peter Sellers) were not involved with The Telegoons production, which mainly relied on the abilities of experienced film makers and puppeteers. Also, since The Telegoons were based on a rework of existing Goon Show scripts, almost for the first time in his life, Spike Milligan was able to work on a Goon project without the additional strain of script writing. By now the Goons, and particularly Peter Sellers (who'd had 21 film offers in the previous year), were each very busy in their own post-Goon Show careers, so if their time commitment to the project had not been fairly minimal, production would probably never have gotten off the ground. Also by this time, the Goons were no longer inexpensive, and received the highest fees the BBC had ever paid for a series of 15-minute shows. Commenting on the immense amount of effort involved in getting The Telegoons production started, producer Tony Young (40) said (Daily Mail, March 30, 1963), "It took three years of planning to get these chaps together. They don't work for peanuts, you know." Tony Young already knew the Goons, having directed them in their first appearance on the silver screen, the 1951 British knockabout comedy film Penny Points to Paradise (see the FAQ section). A veteran of six feature films, Tony Young brought considerable film directing and script-writing experience to the project. His third film, Hands of Destiny (Grosvenor Films, 1954) had also included producer experience. Tony Young produced all of The Telegoons episodes except for the pilot, which was produced by Wendy Danielli (one of the other principals of Grosvenor Films). He also directed eighteen of The Telegoons episodes, with direction of the remaining eight split between Bill Freshman and Michael Wilson. The production cost for the pilot film, The Lost Colony, was ?20,000, mostly raised from private sources. The remaining twenty-five episodes cost ?10,000 each, for a total of ?250,000. The BBC is believed to have secured the British rights for more than ?150,000. To get equivalent 1999 values, these figures need to be multiplied by five, giving a cost of ?1,350,000 (almost US$2,000,000), for the entire production.

|

Suggestion for a wall plaque to commemorate The Telegoons, filmed in the On-The-Spot Lighting building, Kensal Road, 1963.

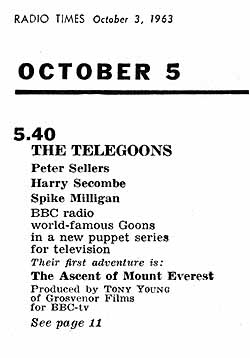

at 5:40 pm on Saturday, October 5th, 1963. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Back to Top

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

'After Blue Streak We Give You Brown Stain...' |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| On the 29th of March 1963,

a major press confab was arranged at The

Telegoons sound recording studios in London. It part it was to

celebrate the

important event of the Goons getting back together again to complete the recording of puppet voices for The Telegoons. It was also to help make Peter

feel welcomed. Incredibly, it was the first time the Goons had worked together since

The Goon Show ended three

years previously. The venue was a sound recording studio in Teddington, and

in some ways the exercise

was not very different from the old Goon Show recording sessions in the BBC Camden Theater. In

other ways, particularly due to time pressure and the lack of a studio

audience, it was very different. The Daily Mail

for Saturday, March

30th, 1963, documented for posterity part of this sound recording session.

Peter started the recording session in his Grytpype-Thynne voice, "And now

by way of hysteria, Britain's latest deterrent....

After Blue Streak we give you Brown Stain..." The newspaper account

of this hilarious session, edited for tense, and somewhat rearranged to conform to the actual

recording, is presented in the sidebar. The episode was Scradge (T.G. 2nd series, #1), based

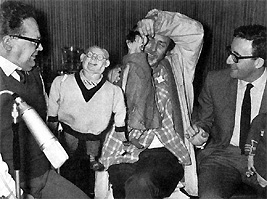

on the radio Goon Show of the same name. A pair of photographs taken

at this recording session are shown below.

In the weeks before the much publicized reunion in the sound studio, Harry Secombe and Spike Milligan had been recording the voices together with a Sellers impressionist, and by March 29th they had completed at least the first thirteen episodes. A stand-in had been used because Peter, possibly due to his commitments with Doctor Strangelove, had been playing somewhat hard to get. Apparently it was with Harry's urging that Peter finally agreed to join the recording sessions. This allowed the last thirteen or so episodes to be recorded with all three of the Goons. Peter to his credit continued on afterwards to dub in all of his parts in the earlier episodes.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Back to Top

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Puppet Lip-Synch Story... |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

With the introduction of lower cost and better performing television sets, as well as an expanded broadcasting network, the post WWII British television audience quickly became more numerous as well as increasingly sophisticated. Gone was television's fairly limited "window on the world" mindset. The viewers wanted entertainment, and it was no longer sufficient to just present traditional entertainments such as one might find at the local repertory theatre, music hall, or puppet stage. Towards the end of the 1950s, television puppetry was still a good audience draw, but there was a growing need to present puppet characters in a more realistic way than the likes of Muffin the Mule and Bill & Ben, the Flowerpot Men. The most important development in this direction was the simulation of human speech movements through a technology called automatic lip synchronization (lip-synch), made possible by then recent advances in electronics and miniature electromagnetic solenoid actuators. Working independently of each other, the two most innovative researchers in this area were Ron Field of the Field Marionettes company (based in Highgate), and Gerry Anderson of Anderson Provis Productions (AP Productions for short, later to become AP Films), based in Maidenhead. The lip-synch electronics system developed by Ron Field overlapped in capability with the electronics package developed by Gerry Anderson. Both systems operated their respective puppet mouth solenoids in step with the syllabic structure of prerecorded dialogue played from a magnetic tape, and both could, through a system of routing switches, operate several puppets at once (as long as they spoke in an orderly manner, one at a time!). A short film clip of the AP Films lip-synch machine appears in a 1965 documentary, The Making of Thunderbirds, which appears on Vol.12 of the "Gerry Anderson's Original Cult Classic Thunderbirds" DVD. What I find particularly interesting about the clip is that although a dialogue tape is being played on the machine, and we can hear the audio that the operator is hearing (unfortunately not synchronized to the picture), the operator is manually operating the lip synch solenoids, while also reading the shooting script. (If you watch closely, you'll see two separate switches being operated for the two sides of the conversation, respectively. The lip-synch puppet head mounted on the machine is slaved to both sides of the conversation so that the operator can check how well the machine is working.) It's possible that Gerry found the manually operated lip synch to be superior to the automatic system. One potential advantage for the manual method is that more than one puppet could speak at one time! Ron Field's lip-synch system (which was patented in 1961, see below) was developed with the assistance of electrical engineer Chris Meader, who built the various working models. Ron first used this system for a puppet circus film pilot in the late 1950s (see pictures in sidebar), and subsequently made it available to Grosvenor Films for use in The Telegoons. Unlike Gerry Anderson's AP Films puppets, the Telegoon rod puppets (which were half life-size half-puppets with no legs) had additional solenoid mechanisms that allowed independent control of the left and right eyelids. This, together with the Telegoon puppets' soft latex rubber faces, lent a degree of realism not possessed by the Anderson puppets. A further difference between the Telegoon puppets and those used at AP Films, relates to the way the puppets' electromechanical systems were powered:

Gerry Anderson's puppet lip-synch system was used in numerous television puppet series made by AP Films during the 1960s. The first AP Films television series to be completely based on this technology was Four Feather Falls, which, in February 1960, introduced the viewing public to the basic techniques of Supermarionation, a term coined by Gerry Anderson during the filming of his next series, Supercar. Supercar's end credits did not bear the words, 'Filmed in Supermarionation' until episodes from the second filming series were broadcast, in October 1961. Supermarionation, which was derived as a combination of "super", "marionette" and "animation", used very fine wires made of tungsten in place of the more conventional puppet strings. Not only were the wires less visible on the television screen, but they also provided a convenient path for the electrical pulses which controlled the mouth solenoid. The "animation" in Supermarionation referred to the puppets' electronic lip-synch capability. Given that AP Films (which became Century 21 Productions towards the end of 1966) held the details of their Supermarionation system a closely guarded secret until well into the 1970s, it is likely that Ron Field's lip-synch work in the late 1950s was conducted quite independently. And even though AP Films (whose studio during the late 1950s at Islet Park, Maidenhead, West London), was situated only about 24 miles (38 km) from Ron Field's home and workshop in Highgate, North London, the communication grapevine then was not as developed as it is in these days of e-mail and private facsimile machines. The tight secrecy around AP Films' Supermarionation techniques might have prevented Ron Field from finding out very much, other than the little that could be guessed from viewing the television programmes that they produced. After all, it is difficult to tell good manual lip-synch technique from automatic lip-synch just by watching the results on a small television screen! I've no doubt too that Ron would have been fairly secretive about his own work, which would have prevented information flowing the other way as well. Ron Field's patents, Improvements in Dolls, Puppets, Toy Animals and the like (GB 965,916 and GB 965,917), which were applied for on March 22, 1961, and granted on August 6, 1964, do not mention any kind of automatic lip-synch as prior art, despite the fact that, thanks to the wildly popular Supercar television series, the new word "Supermarionation" was already in the public's vocabulary. AP Films promotional literature of the time described Supermarionation process as "A new TV discovery!" Supercar, it went on, was "The first all-electronic series, with miniature characters in perfect synchronization!" (Gerry Anderson The Authorised Biography, Archer & Nicholls, 1996, p.50). Yet, the only prior art mentioned in the Field patents concerns hinged mouths using a manually-operated pull-wire to achieve lip-synch. Ron Field's automatic lip-synch system (which despite its early date, was fully transistorized, by-the-way!) was fully automatic, and (as was described in his patents) able to control multiple puppets from a single recorded dialogue track using a series of manually operated routing switches. Years later it was revealed that the AP Films Supermarionation system had a similar capability (ibid., p.42). Although Ron Field described a completely automated puppet lip-synch system in his patents, his unique claim related to a special construction method for puppet heads. This gave very natural-looking facial movements during simulated speech (automatically lip-synched or otherwise). Contrasting this with Gerry Anderson's Supermarionation puppets, all of which had a stiff fiberglass-resin head and a stiff-but-moveable lower lip (giving a quite different and much less realistic effect), it would seem that Ron Field was indeed traveling down his own independent path of invention. Probably very aware of the commercial advantage of keeping the Supermarionation technology as a trade secret, rather than applying for a (very much more public) patent, Gerry Anderson did not apply for a patent until 1977, and then it was for a new development in puppet lip-synch, namely proportional control of the mouth position. As near as can be determined at present, Ron's pioneering work in electronic lip

synch took place at about the same time as and independently of Gerry Anderson's own pioneering work,

probably in the 1958/59 timeframe. Ron's first use of his automatic lip-synch invention

can be dated by its use in the previously mentioned pilot film for a series of television puppet circus

films in the late 1950s, and a lot of development work on the invention would have preceded the

circus pilot. Gerry Anderson, on-the-other-hand, started experimenting with his automatic lip-synch

system during the northern winter of 1958/59, in the later episodes of Roberta Leigh's first series of Torchy the Battery

Boy, produced by Gerry's AP Films. (See timeline at the S.I.G.

website here).

An interesting vignette about AP Films' lip-synch developments was

provided by Jan Bussell, editor of The Puppet Master (the magazine of the

British Puppet and Model Theatre Guild), in the October 1959 issue. After

mentioning Roberta Leigh's departure to make a second series of Torchy

with a different company, he writes, "Meanwhile the original

Torchy group [AP Films] is reported to be working on a new series

of programmes, but an unusual air of mystery at present surrounds their

activities. There are reports of electronically operated mouths . . .

." All very mysterious sounding, but helpful in putting the

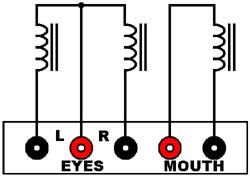

historical record straight. ---oOOOo--- The Telegoon rod puppets used three electromagnetic solenoid actuators to accomplish mouth and eyelid movements, mounted inside the head of the puppet (see "X-Ray" view of the Neddie Seagoon puppet here). Finger-operated switches for controlling the solenoids were mounted on a handheld control. This control was held in one hand, while the other hand reached inside the puppet's body to operate the head control rod (which, at least on the Neddie Seagoon puppet, also included a mechanical thumb lever for controlling side-to-side eye movements). When the electric current to a solenoid was switched on, the mouth or corresponding eyelid would open; when the current was switched off, it would relax and close again. Most likely in the interests of keeping things simple for the puppeteers, normally only two switches were used, one for the mouth, and the other for controlling both eyelids simultaneously. The trick for the puppeteers was learning to operate the mouth switch in time with the syllables of the dialogue, while remembering to do everything else as well! A significant problem was that no two puppets had the exactly same mechanism inside. As recalled by Violet Philpott, "We would go in a corner [to practice] with a particular puppet we might be working. And it wasn't a constant thing, we didn't have one particular one. You might be given any of them, and the mechanisms were all different...because [the makers] were still experimenting with them to find the best. ...maybe one bit would work with the finger, and another with the thumb, and things like that. Like a handle with triggers and things" When I asked for more specifics on the design of the controls, Violet said, "...they were varied...and it was quite difficult, really, because of the variety. Violet further went on to say that after practicing with one puppet, "So you would think [the puppets all] work like this, but then you would get another puppet given to you, and you'd find a different mechanism inside.... Also, of course, you'd have the script in front of you, and you'd be looking at your script, and raggling away with the figure, and they'd say, 'Right, we'll go for a take, and get it together'. Then [the producers] learned that it was impossible because as soon as you heard the tape, it didn't tally with the script, because of the ad-libbing of the Goons. You see, you can't tie them to a script, it's not their way. But you would have thought [the producers] would have worked from the tapes and transposed the tapes into printed words for us." It is probably for these reasons that the quality of lip-synching in the earlier episodes in the filming sequence is somewhat variable. Getting the Goons back to re-record lines was, for various reasons (such as time, money, and the sheer improbability of pulling it off for it a second time), clearly out of the question. Post-production had to make do with what they already had. The unavailability of automatic lip-synch during the first fourteen or so Telegoons episodes was an inconvenience that grew into a major headache, especially in post production. However, a more fundamental problem was that the shooting scripts did not match the dialogue tapes. The Goons had a well known tendency to ad lib, and probably this should have been taken into account. If the shooting scripts had been updated to reflect the final recorded dialogue, then all would probably have been well. As it was, the puppeteers would do a listen-through on (usually) Monday morning, marking relevant corrections on the shooting script. Compared to the radio shows, where adlibbing had been one of keys to the Goons' immense success, in the more contrived and rehearsed world of television puppets it was a disaster. Apart from the disruption this caused during shooting, in post production the problem was much worse. Not only did the dialogue not match the shooting script, but the puppeteers attempts to keep up with the dialogue was not always perfect. Any sort of deviation from the shooting script made attempts to match the recorded dialogue to the puppets' mouth movements captured on film, extremely challenging. Had automatic lip-synch been used from the beginning, there would have been less necessary to update the shooting scripts. The time and energy that the puppeteers put into manually synchronizing the puppets' mouth movements with the rhythm of the scripted dialogue was often derailed because there was little or no opportunity for the puppeteers to rehearse with the tape before each take (remember that this was years before the advent of portable, low-cost tape recorders). So, when a final run through was performed, the recorded dialogue was often being heard by the puppeteers for the first time. Any ad-libbing on the tape meant that the puppeteers had to try and modify their carefully rehearsed movements, including the all-important manual lip-synch, "on-the-fly." This method of working proved very difficult because the puppeteers didn't know what the Telegoon characters were going to say until they actually said it. In addition, the puppeteers found it quite difficult to keep up, especially with Ned Seagoon, who talks faster than any of the other characters (and faster than most people other than Harry Secombe). About half-way through the production (starting with the seventeenth episode), automatic lip-synch was finally deployed, and manual lip-synching of the puppets was discontinued. This breakthrough made life a lot easier for the puppeteers, who now had one less thing to worry about. However, the real benefit came in post production, because now the mouth movements always matched the dialogue! Before leaving the topic of automation, it is worth noting that it extended only to the mouth movements; the puppeteers still retained full manual control over the electrical left- and right-hand eyelid mechanisms, usually controlled together with a single switch. Determining which episodes were made with automatic lip-synch and which were lip-synched manually is fairly straightforward. For starters, the shooting scripts for the first seventeen episodes still exist, and these are marked with a script serial number (see table in sidebar). When these serial numbers are combined with the film credits, it is easy to determine who did what and when. The first thing to be noticed is that the filming order is quite different from the order in which the episodes were broadcast. This is quite normal for a television series consisting of unconnected episodes, and indeed the broadcast varied somewhat different in the various markets the films were sold into. Regarding lip-synch, Violet Philpott said that it was done manually during her entire time with the project (although there is evidence that it was introduced in Violet's last three episodes). As had been pre-arranged, after fifteen episodes (scripts 1 through 15, see sidebar) Violet left the production, in order to attend the first international puppetry festival at Colwyn Bay, Wales. We also know that John Dudley stayed on for two more episodes, leaving to present the Dudley Marionettes at Coventry Gala and Carnival on June 15th, the first of several summer engagements. He recalls that automatic lip-synch was introduced during his last four episodes (T.G. scripts N.14 to Q.17, see sidebar). With the departure of John Dudley, the project's only remaining professional puppeteer was gone. It is very likely, therefore, that all of these episodes used the automatic lip-synch system. The filming order for the last eight episodes is still unknown, and will probably remain that way unless the relevant shooting scripts (#18 through #25) come to light. The above discussion about lip-synching applies

principally to the half life-size rod

puppets, which were designed for use in close-up shots. They also built third life-size string

puppet versions of the characters for

medium and wide shots. Whether or not the Telegoon

string puppets had magnetic solenoid mechanisms is a matter for future study. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Back to Top

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Tale of the Revised Pilot Film... |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The 2nd broadcast episode, The Lost Colony (T.G. 1st series, #2) is a modified (and heavily cut) version of the 33:00 pilot film of the same name. Made three years earlier at a cost of ?20,000 in private money, the pilot secured funding from the BBC for production of the series. The puppeteers on the pilot were Ron Field, Joan Field, and Ann Field (all of whom were uncredited in the broadcast version). Only one of the pilot puppeteers, Ann Field, was a puppeteer on the series. Continuity for the pilot was done by director Tony Young's wife, Doreen Dearnaley (uncredited). One of three "assistants" employed to help with changes to the

pilot film for broadcast was puppeteer Joan Garrick, of Space Patrol (UK) fame.

Joan's contribution was as puppeteer in the 1:40 Christopher Columbus opening

sequence (opening sketch), which sets up the plot and provides a quick laugh or

two to warm up the audience. A 10 second linking scene with

Grytpype-Thynne in his soon-to-be-familiar role as announcer, manipulated by John Dudley (uncredited), was added at the

end of the Columbus sequence. Based on the success of this composite opening sequence, a similar

format was used to good effect on

all subsequent episodes in the series. The title sequence for this episode says that it was produced by Wendy Danielli, in association with Tony Young. This simply reflects that it was Wendy who arranged the private financing of the pilot. However, after funding for the series was obtained from the BBC, all subsequent episodes were produced by Tony Young, with Wendy Danielli as associate producer. All available evidence suggests that the pilot film's soundtrack was in fact the radio Goon Show recording, The Sale of Manhattan (G.S. 6th series, #11) (which, by-the-way, was announced on that show as "The Lost Colony"). One fairly reliable source, the Radio Times Guide to TV Comedy (see Bibliography section), says it is thought that The Telegoons used extracts from the original BBC recordings of the radio Goon Show. Since no amount of listening has shown any commonality, this rumour probably arose from the way that the pilot film was made, and does not apply to the episodes which followed, all of which have newly recorded soundtracks based on Maurice Wiltshire's rewrites of the original radio scripts. In any case, it is unlikely that the Goons would have recorded a one-off soundtrack for the pilot (see discussion in the Misconceptions section), particularly since pilot puppeteer Ann Field remembers director Tony Young planning to "make a killing" by reusing the Goon Show recordings (thereby saving the huge cost of rerecording them). Ann also recalls that the pilot was shot using a dialogue tape with the Goons' voices. She also confirmed that the pilot film was something like 33 minutes long, and that, "The [relatively slow] speed of the puppet movement was the main concern for all," all of which rather clinches the matter. To further strengthen this assumption, I have done a trial edit of the first few minutes of The Sale of Manhattan episode of the radio Goon Show, and have not been too surprised by how well it matches the film footage in the 1963 broadcast episode. Nevertheless, the largest modification of the pilot film was not the addition of an opening sequence, nor was it the deletion of more than 18 minutes of footage. Nor was it the changes to the credits. Instead, sometime in early 1963, the old 1960 soundtrack was replaced with a newly recorded one that better took into account the speed of the puppets, also providing uniformity of style with the other episodes. The difficulties of synchronizing the dialogue with the pre-existing film footage (which don't exist if the dialogue is recorded first) were exacerbated by the Goons' tendency to ad lib. For similar reasons it must also have been difficult to match up Peter Sellers' dialogue for the first eight episodes filmed, which due to his delayed arrival at the voice recording sessions, had been done by a stand-in. Study of the scripts shows that even the stand-in did some ad-libbing (noted by the puppeteers prior to doing the lip-synch manually, as was done in the early episodes). After the dialogue recordings for the remaining episodes were completed, Peter, probably now in full swing, went back and re-recorded his parts for the first episodes (see above). I can only imagine the effect this must have had on the dubbing department! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Back to Top

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A Family Affair... |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| At some point during the sound recording sessions for The Telegoons (possibly right after he

arrived from doing Doctor Strangelove), Peter Sellers had lodgings with Mr. and

Mrs. Ralph Young, at their home "Midhurst", on the Towpath at Shepperton Lock on

the River Thames. This modest home provided an idyllic retreat (see photograph) far away from

the hustle and bustle of Central London.

As well as being the father of producer/director Tony Young, Ralph Young was the co-developer (with Ron Field) of the Telegoon puppets. Moreover, while it is principally the Goons' and particularly Spike Milligan's mental images and drawings of the Goon Show characters that influenced the puppets' physical form, it is possible that Ralph Young may have assisted an unknown sculptor with the original plasticine sculptures or at least have assisted with the fabrication of the foam rubber latex heads. One indication that Ralph put a lot of himself into the puppets is the story that years after The Telegoons television series ended, many of the string puppet heads still adorned a large shelf in Ralph Young's living room. More than one visitor to Midhurst thought that the puppets heads were "very creepy". |

Ralph Young's home, Midhurst, at Shepperton Lock. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tony Young (Ralph Young's eldest son) was producer for The Telegoons, and also directed most of the episodes. After a film career spanning 1951 - 1964, Tony Young died of cancer in the late 1960s around age 47. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| David Young (youngest son of Ralph Young, and younger than big brother Tony by ten years) was the puppets supervisor for The Telegoons. He lived just two doors along from his parents home, in "Lock View". David helped his father Ralph build the puppets. It is also possible that David helped design the puppets, as he was a very creative, if not somewhat unconventional individual. As an example, for many years David lived in a gypsy caravan bolted onto the rear of his house, rather than living in the house itself! After The Telegoons, David Young and his wife Tina Williams owned several restaurants in the Shepperton / Sunbury / Twickenham area. The first of these, a jazz restaurant called Nellie McQueens (now Bar 41), situated in Lower Sunbury-on-Thames, had several of the Telegoons puppets adorning the premises until it finally closed, probably in 1993. Nellie McQueens was quite famous for its jazz-theme decor and live music, and was frequented by minor celebrities in the entertainment industry. David's second jazz restaurant, Dixie McQueens (now Murrays), was situated in York Street, Twickenham. Apparently when Dixie's was opened, some or all of the puppets were transferred there, and sat in a wicker basket on the bar. This information came from Alan P. who had helped David remodel both Nellie's and Dixie's. He said, "I liked seeing them slowly disintegrate. They were quite a centerpiece at the bar." David Young died of cancer in 1992 around age 63. Tina, unable to keep both restaurants open, closed Dixie's. About a year after that, Nellie's ended up being closed as well. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||